* * *

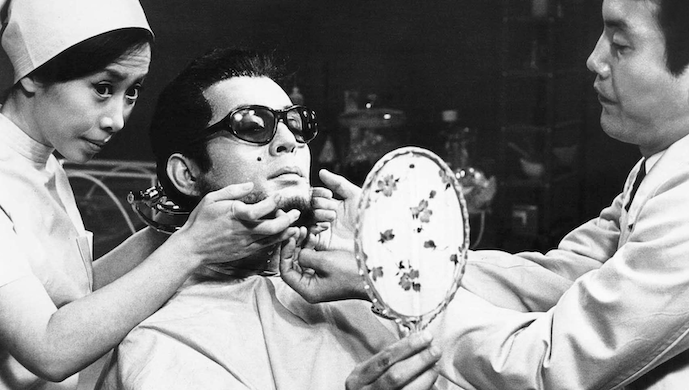

The backstory for “Classe Tous Risques” (1960) is, as the young folks say, problematic. Overseen by a French director, Claude Sautet, this gangster picture is based on a 1958 novel of the same name by José Giovanni. Therein lies a complicated tale.

Monsieur Giovanni was, in actuality, Joseph Damiani, a Corsican by descent with an elite Parisian education, a tendency for duplicity, and a keen disregard for human life. What kind of villainy didn’t he engage in?

His membership in the Vichy youth group Jeunesse et Montagne was the least of it. Not only did Damiani join the Nazi-adjacent French Popular Front and the Nazi-sponsored Schutzkorps, he was an active hand at blackmail and murder — with Jews being a particular point of focus.

Apprehended by the authorities, Damiani was found guilty of murder. Only a last-minute reprieve saved him from the guillotine. Twenty years of hard labor was downgraded to 11 and a half time-served, after which Damiani adopted the “Giovanni” nom de plume and began writing novels and screenplays.

Giovanni’s underworld experience fell neatly in line with a cadre of French filmmakers enamored of the illicit allure of life outside the law. Giovanni was one of the screenwriters, along with Sautet and Pascal Jardin, of “Class Tous Risques,” which will be undergoing a six-day revival at Film Forum starting March 15.

* * *

Giovanni’s participation undoubtedly counts for the film’s sui generis status. As a gangland epic, the story is oddly intimate, imbued, as it is, with a distinct sense of the human toll exacted from life-on-the-run. Part-and-parcel of that intimacy is the ready application of brutality. Should a person prove unsuitable to one’s plans, that same person can summarily be tossed overboard.

That is exactly what happens to the captain of the speedboat unlucky enough to pick up two hardened criminals, Abel Davos (Lino Ventura) and Raymond Naldi (Stan Krol). Among those accompanying them are Davos’s wife Thérèse (Simone France) and their young sons Pierrot and Daniel (Robert Desnoux and Thierry Lavoye). Upon arriving on shore, a shootout ensues between the gangsters and a pair of customs officials. The only survivors are Davos and the boys. Word gets out of the murders and a manhunt traversing Italy and France commences.

Davos puts out word to a nucleus of former associates that he’s in need of safe passage to Paris. Each of these contacts are men for whom Davos has done significant favors — and each of them, in this instance, blinks. They ultimately decide to hire someone outside of their circle, a solitary thief by the name of Éric Stark (Jean Paul Belmondo).

The plan is for Stark, posing as an ambulance driver, to bring his “patient” Davos for medical care in the city — a ruse that proves effective in getting past police roadblocks. It doesn’t hurt that a woman they’ve picked up on the way, Liliane (Sandra Milo), is an actress. Liliane, smitten with Stark, helps our anti-heroes by posing as a nurse.

Cervantes wrote that “thieves are never rogues amongst themselves,” but tell that to the motley crew of underworld types who are chagrined when Stark actually succeeds in bringing their former partner-in-crime back to Paris. Davos is livid at their lack of loyalty, but he’s also in desperate straits: The law is closing in. One more big score should be enough to make it away clean. Stark is the only man Davos can trust.

Belmondo had yet to make a splash with “Breathless” (1960), but he inveigles himself into every scene here, playing off Ventura’s brooding thunder with a devil-may-care insouciance.

The picture ends on a note that seems redolent of studio interference, and the oddments of voice-over narration feel tacked on. Still, “Classe Tous Risques” is an engaging amalgam, by turns casual and a hurly-burly, of documentary-like verisimilitude and sunlit noir. If you’re in the mood to witness a turning point at which old school wise-guys were upended by new school cool, this movie is an entertaining place to start.

(c) 2024 Mario Naves

This review was originally published in the March 12, 2024 edition of “The New York Sun.”